Star Atlas Mystery: The Bečvář 14

by Doug Reilly / January 17, 2013

http://theonlineastronomer.com/2013/01/17/star-atlas-mystery-the-becvar-14/

Astronomers active between roughly 1950 and 1980 all know who Antonín Bečvář is, though they probably can’t say his last name with the correct Czech pronunciation (Betz-VOSH–but with a weird trill on the sh). His Atlas Coeli Skalnate Pleso, known around these parts as the Skalnate Pleso Atlas of the Heavens, plotted the stars, nebula, galaxies and star clusters of the night sky in 16 large-format charts that were hand-drawn by Bečvář himself. A gaggle of students assisted him in compiling the coordinates of the stars and deep sky objects that would be included on the map…the most detailed full-sky map ever attempted at that point. The team worked at the Skalnate Pleso observatory in the Tatra mountains of Slovakia.

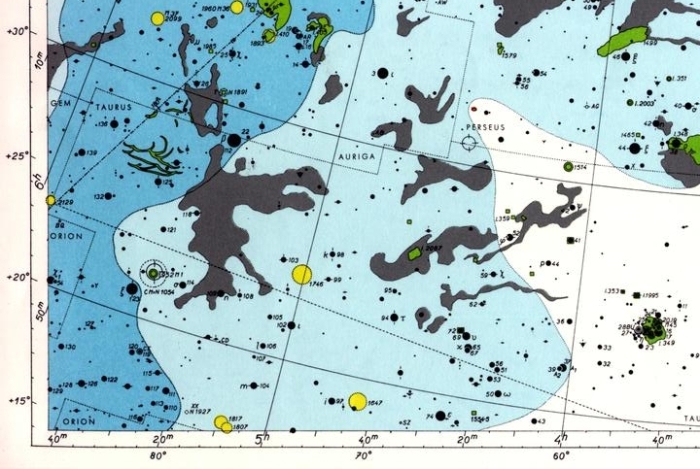

The Skalnate Pleso atlas quickly became the go-to star map for astronomers both professional and amateur. Since it charted most objects that could be viewed with an 8″ telescope, which at that time was considered to be a “large aperture” telescope, the Skalnate Pleso was the only atlas an observer would ever have to buy. And it was pretty, setting a standard for more modern, clear star charts with a smart use of color:

AC_C

But there are a handful of curious things about the Skalnate Pleso atlas. 14 of them, to be precise. They are: Achird, Arich, Haris, Hasseleh, Hatysa, Heze, Kaffa, Kraz, Ksora, Kuma, Reda, Sarin, Segin and Tyl, and they are proper star names, many of which remain in common usage today. They seem to have originated in the Skalnate Pleso atlas, though who named them and what the names might mean is shrouded in a mystery so thick that the largest ground-based telescopes and even the orbiting Great Observatories are powerless to resolve the issue.

Most star names are very old, sometimes dating back to the Assyrians, and they have been passed down in various Arabic, Greek and Latin sources. Many proper star names have Arabic origins: Altair, for instance which comes from an-nasr aṭ-ṭā’ir (English: The flying eagle). Star names can have particularly torturous etymologies. Consider Albireo, which sounds Arabic but isn’t. The people who study star names have obviously steeled themselves to the most complex linguistic histories, but the Bečvář 14 have them completely stymied. They can find no earlier reference to these names than the Skalnate Pleso atlas, and moreover all but two of the names themselves seem to have no clear etymology (and for the two that do, Haris and Segin, nothing is conclusive).

I first learned of the strange origin of these star names from Dana Wilde’s book Nebulae; A Backyard Cosmography, which I will be reviewing soon here. Dana kindly told me everything he knew about the star names, which is not much more than what I wrote above. My wife, who is Slovak, spent a few nights looking for Slovak-language references to the star names, and came up with nothing, though she did find some fascinating biographical information about Bečvář himself.

Where the 14 star names a flight of fancy by Bečvář, something he dreamed up while pursuing his main expertise, which was mountain cloud morphology? Or worse, was it an elaborate joke? A coded message to the west from a scientist behind the Iron Curtain? Was he enshrining the nicknames of teenage girlfriends? Or places from his childhood home that only existed in local dialect?

The origin might not have been Bečvář at all–it could have been one or more of the students who were helping him compile the catalog at Skalnate Pleso. And lastly, there may have existed an older source, known to Bečvář and/or his team, that simply isn’t part of the current library of historical star charts. Is that source Slavic, or even Chinese?

We have no idea.

It’s a intriguing mystery. The names are pretty. They look and sound like they mean something. How the heck did they get there? I’d love to know.

Maybe one of my readers has some information. If so, let me know. In the meanwhile, these have become my favorite 14 star names, beating out even good old Zubenelgenubi, which sounds awesome but has roots so thoroughly documented that it’s boring. I’m going to observe all 14, and maybe one day, when I’m in Slovakia, might try to take up the trail of the Bečvář 14.

Here is the result of my own quick lookup on Google, with the stars listed along with their Bayer designations. Many of these stars also have more well-known traditional or historical names (mostly from Arabic or Greek). For example, Kaffa is also known as Megrez.

Achird – Eta Cassiopeia,

Arich – Gamma Virginis

Haris – Gamma Boötis

Hasseleh – Iota Aurigae

Hatysa – Iota Orionis

Heze – Zeta Virginis

Kaffa – Delta Ursae Majoris

Kraz – Beta Corvi

Ksora – Delta Cassiopeia

Kuma – Nu Draconis

Reda – Gamma Aquilae

Sarin – Delta Herculs

Segin – Epsilon Cassiopeia

Tyl – Epsilon Draconis

The Becvar 14 may simply be copyright traps. Piracy of star charts has been around for centuries. Other anomalistic names have crept into astronomical lore. In the southern hemisphere, where there is no ancient history of star names, navigators have made up their own. For example, Alpha Pavonis, the brightest star in Pavo, the Peacock, is listed simply as “Peacock” in the Nautical Almanac. Alpha Triangulum is also shortened to “Atria”.

Alpha and Beta Delphinus were first catalogued in 1814 as “Sualocin” and “Rotanev”, or “Nicolaus Venator” spelled backwards. The name is the Latinized (and now immortal) version of “Niccollo Cacciatore” (English: Nick Hunter), a lowly astronomical scrivener who worked on the Palermo Catalogue. I understand this one gave antiquarians and linguists fits for over a century. They have eyes trained to detect anagrams, but the childhood trick of spelling something in reverse snuck right past them.

I have the 1964 Sky Publishing edition of the Becvar Atlas, but the traditional star names are not listed there, only their Bayer or Flamsteed numbers. Although a bit out of date today, the Becvar atlas is still useful for naked eye or binocular astronomy, and is still unsurpassed as an esthetic masterpiece. It is a fine example of both the uranographer’s and printer’s art.

-

Nice story.

- Astronomy not only has data; it also has lore.