The Milky Way’s Quiet, Introverted Monster Won’t Spin

Many black holes spin much faster than this.

By Rafi Letzter | Live Science Staff WriterOCTOBER 26, 2020 | There’s a beast hiding at the center of the Milky Way, and it’s barely moving.

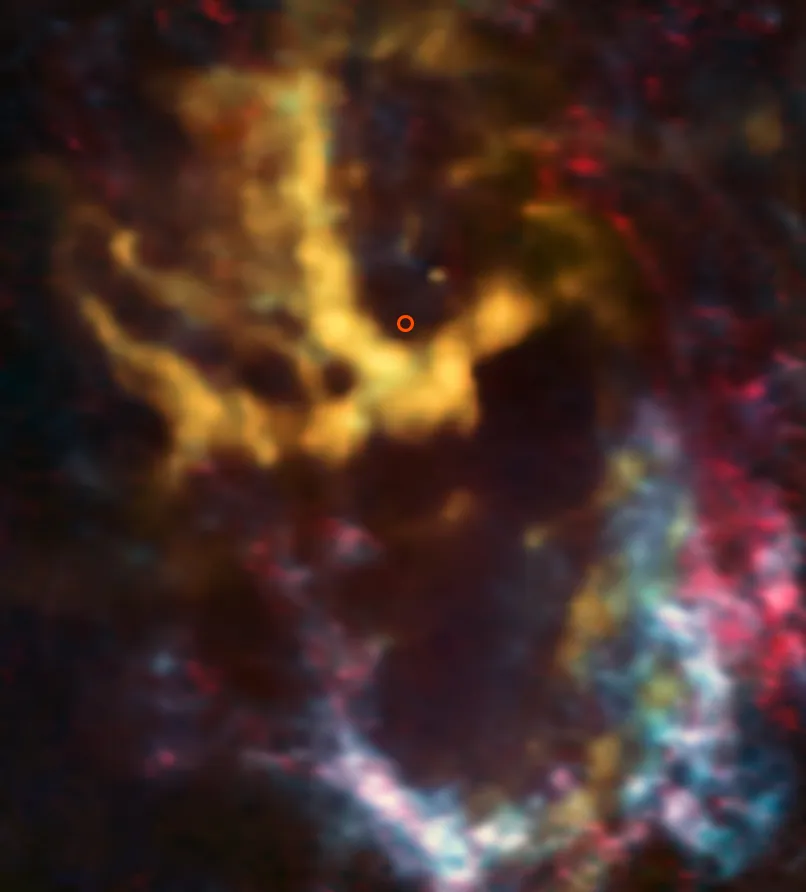

An image from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) shows molecular gas clouds around the region where the Milky Way’s central, supermassive black hole is known to exist. That region, highlighted in red, looks dark and silent.

(Image: © ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/ J. R. Goicoechea (Instituto de Física Fundamental, CSIC, Spain))This supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A* (SgrA*), has a mass 4.15 million times that of our sun. It first revealed itself to scientists as a mysterious source of radio waves from the galaxy’s center back in 1931; but it wasn’t until 2002 that researchers confirmed the radio waves were coming from something massive and compact like a black hole —— a feat that earned them the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics. Just days before the team learned about their Nobel on Oct. 6, another group learned something new about the black hole: It’s spinning more slowly than a supermassive black hole should, moving less than (possibly far less than) 10% of the speed of light.

Black holes, despite their awesome power, are extraordinarily simple objects. All the distinguishing features of the matter that forms and feeds them gets lost in their infinitesimal singularities. So every black hole in the galaxy can be described with just three numbers: mass, spin and charge.

Once researchers locate a black hole in space, measuring the mass is pretty straightforward —— just check how strongly its mass is tugging on nearby objects. To get the mass of SgrA*, scientists just observed its influence on the “S-stars,” a collection of the Milky Way’s innermost stars that get accelerated to incredible speeds as they whip around the black hole in tight orbits. And researchers assume that, like most large objects in space, black holes don’t have strong electromagnetic charges.

(Planet Earth, for example, has some positively charged particles and some negatively charged particles, but they cancel each other out across the whole planet. The other planets and known stars work the same way. Researchers assume black holes are similarly neutral in charge.)

That leaves spin as the remaining measurable feature of SgrA*, and now researchers think they have evidence that the supermassive is an unusually slow spinner.