Abstract: Just more bad news.

The following remarks are excerpted from the NSIDC website.

http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews

Further analysis, maps, charts and tables can be found there.

Sea ice extent in the Bering Sea remains at record low levels for this time of year. Total ice extent over the Arctic Ocean also remains low and consists of a record-high amount of first-year ice. This means the ice cover is unusually thin and large areas are susceptible to melting out in this coming summer.

Arctic sea ice extent for April 2018 averaged 13.71 million square kilometers (5.29 million square miles). This was 980,000 square kilometers (378,400 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average and only 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 square miles) above the record low April extent set in 2016. Given the uncertainty in measurements, NSIDC considers 2016 and 2018 as tying for lowest April sea ice extent on record. As seen throughout the 2017 to 2018 winter, extent remained below average in the Bering Sea and Barents Sea. While retreat was especially pronounced in the Sea of Okhotsk during the month of April, the ice edge was only slightly further north than is typical at this time of year. Sea ice extent in the Bering Sea remains the lowest recorded since at least 1979. The lack of sea ice within this region created many coastal hazards this past winter.

Overall, sea ice extent for April 2018 declined by 920,000 square kilometers (355,000 square miles). The amount of ice lost for the month was less than the 1981 to 2010 average of 1.1 million square kilometers (424,700 square miles). The ice edge retreated everywhere except in Hudson Bay and Baffin Bay/Davis Strait. The sea ice expanded slightly within Davis Strait during the month. Sea ice in the Hudson Bay usually does not begin to retreat until the end of May.

Air temperatures at 925 hPa (about 2,500 feet above sea level) for April were up to 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than average in the East Siberian Sea and stretching towards the pole. Air temperatures were also up to 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) above average within the East Greenland Sea and 3 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) above average over Baffin Bay. By contrast, air temperatures were near average within the Barents and Kara seas and lower than average over Canada and the Hudson Bay. The pattern of temperature departures from average resulted from higher than average sea level pressure over the Beaufort Sea as well as the North Atlantic, combined with below average sea level pressure over Eurasia and western Greenland through eastern Canada. On the Pacific side of the Arctic, this pressure pattern drove warm air from the south over the East Siberian and Chukchi Seas, while bringing cold air into northern Canada. The pattern of above average sea level pressure over the North Atlantic was combined with lower than average sea level pressure over western Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago, bringing in warm air in from the south over Greenland and Baffin Bay.

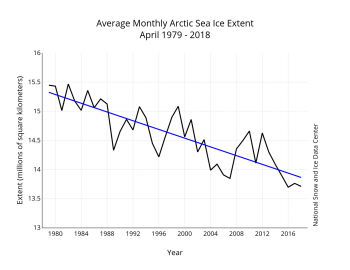

The linear rate of decline for April sea ice extent is 37,500 square kilometers (14,500 square miles) per year, or 2.6 percent per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 average.

An updated assessment of ice age changes through the first nine weeks of 2018 shows there was essentially no multiyear ice within the Beaufort, Chukchi, East Siberian, Laptev, Kara and Barents Seas in early March (Figure 4b). There is only a small tongue of second-year ice extending from near the pole towards the New Siberian Islands. Near the pole, there are large patches of first-year ice among the multiyear ice. As averaged over the Arctic Ocean (Figure 4d), the multiyear ice cover during week nine has declined from 61 percent in 1984 to 14 percent in 2018, the least amount of multiyear ice recorded. In addition, only 1 percent of the ice cover is five years or older, also the least amount recorded. This is rather striking since September 2017 did not set a new record low minimum extent. The proportion of first-year versus multiyear ice in spring will largely depend on the amount of open water left at the end of summer over which first-year ice forms. How much ice is transported out of the Arctic through Fram Strait in winter also plays a role. The unusually high amount of first-year ice this March suggests that there was a strong Fram Strait ice export this past winter. Given that (in the absence of ridging) first-year ice grows to about 1.5 to 2 meters (4.9 to 6.6 feet) thick over a winter season, the ice age data point to a fairly thin ice cover. Nevertheless, how much ice melts out this coming summer will depend strongly on summer weather conditions.

“Multiyear ice” is thick, floating ice that has survived the summer melt season. It forms a nucleus of sea ice on which “first year ice” can accumulate the following winter.